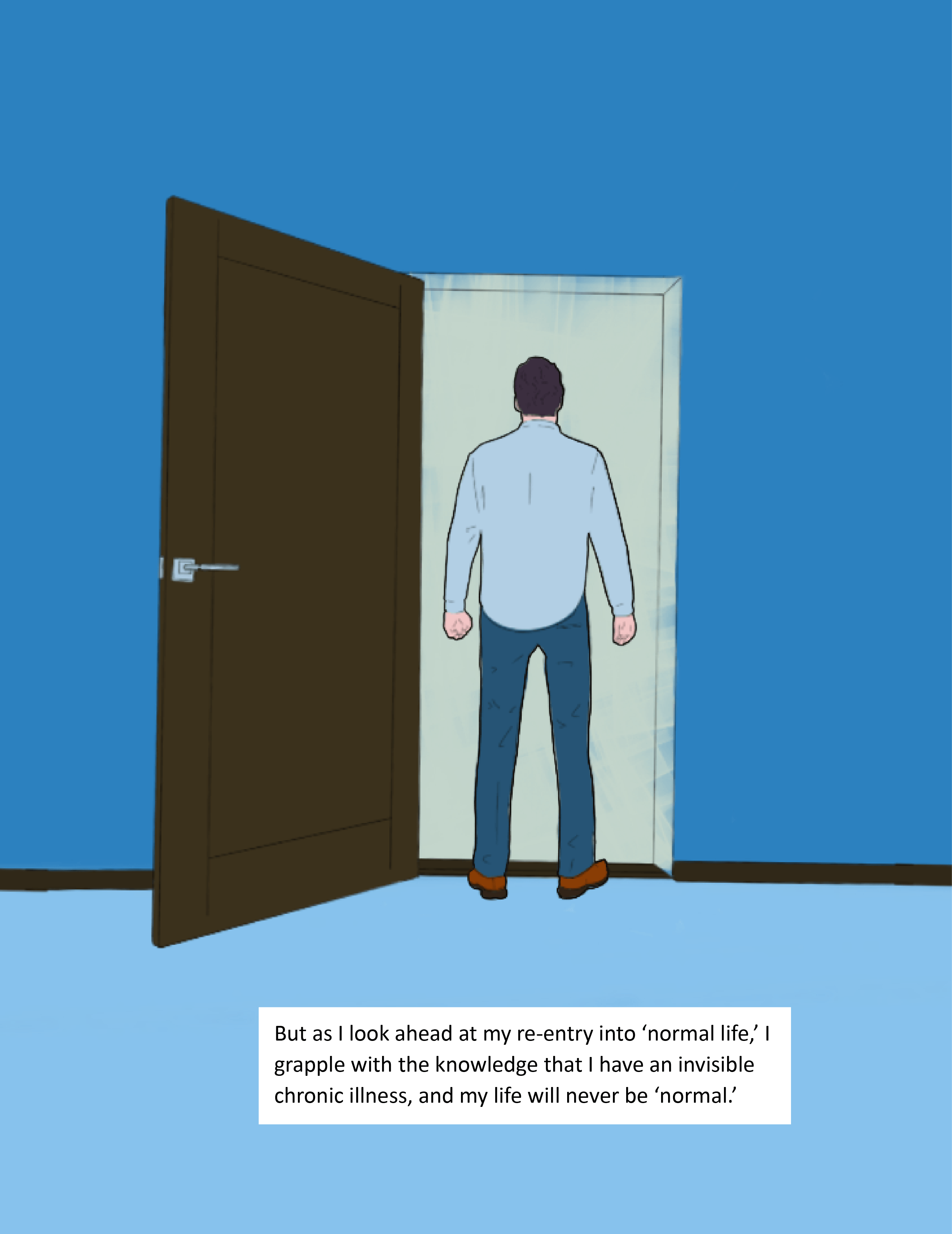

“Hippocrates introduced the historical conception of disease, the idea that diseases have a course, from their first intimations to their climax or crisis, and thence to their happy or fatal resolution. [He] thus introduced the case history, a description, or depiction, of the natural history of disease. Such histories are a form of natural history – but they tell us nothing about the individual and his history; they convey nothing of the person, and the experience of the person, as he faces, and struggles to survive his disease… To restore the human subject at the centre – the suffering, afflicted, fighting human subject – we must deepen a case history to a narrative or tale: only then do we have a ‘who’ as well as a ‘what’, a real person, a patient in relation to disease – in relation to the physical.” – Oliver Sacks (The Man Who Mistook His Wife For a Hat)

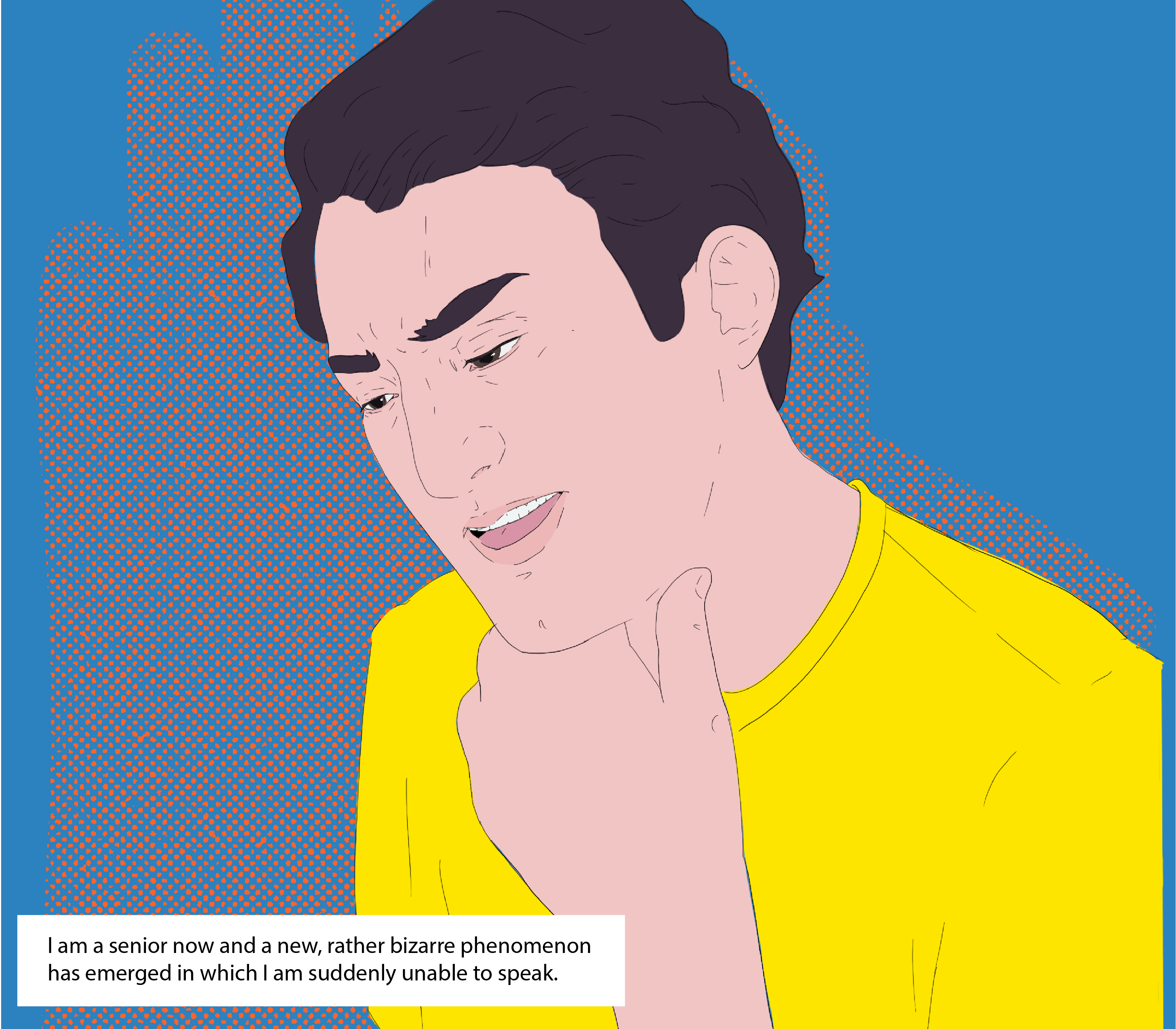

I am a storyteller of sorts. I write music for movies. I write musicals, screenplays, short stories and, at the moment, I’m making my first documentary. I’ve always believed that stories – like math, history and physics – exist independently of our recognition of them. It’s the role of the storyteller, much like the archaeologist, to extract from the chaos of the world, a pattern: a greater truth.