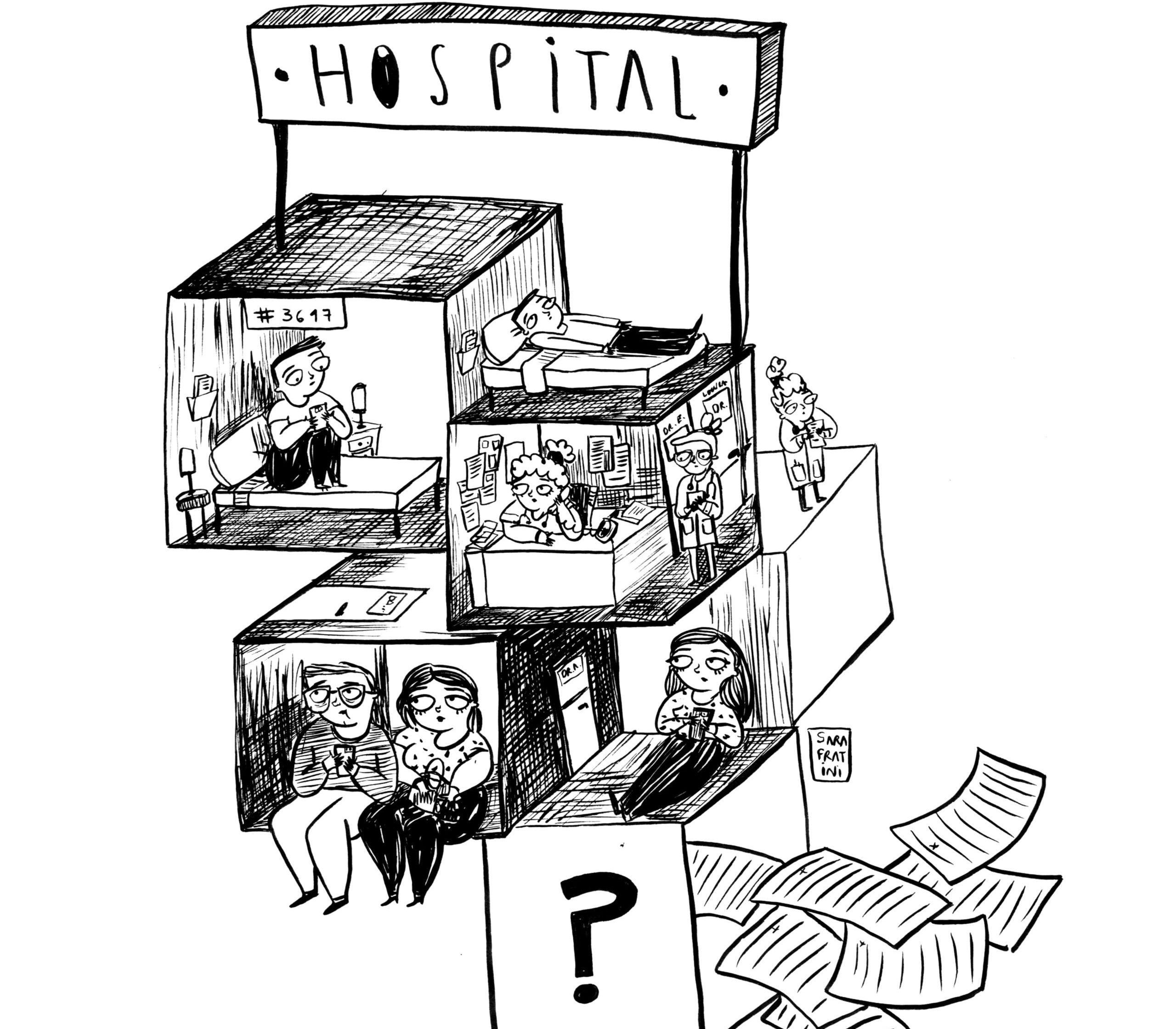

“You sure this is it?” I ask, staring up at the brick building as my family pulls into the parking lot. It looks more like a Holiday Inn than a psychiatric hospital, sitting unassumingly across from a Taco Bell. It’s hard to believe my baby brother is inside.

“Fun fact: It’s a converted motel.” My dad sounds almost cheery, obviously relieved to have company. Yesterday he spent six hours here alone, waiting for my mom and me to arrive. Since my brother G hadn’t signed an information release form yet, the staff couldn’t tell my dad anything, so he sat in the lobby watching reruns of House Hunters and reading glossy pamphlets cover-to-cover. Now my dad parrots back all the “fun facts” he learned about the hospital, and my mom and I pretend to be impressed.

We walk through one set of glass doors, then glimpse a white-haired woman behind a desk who smiles and waves before buzzing us in through another.

“Welcome to Visiting Hours! I’m Sue.” Sue’s voice is a specific type of sunny, the fake kind only found in the Midwest. “Who you here for?”

“#3617.” My dad knows the drill — since they think of my brother as a number, we have to, too.

Sue nods and gestures for us to sit. We do.

“Fun fact: This hospital has 144 beds,” my dad says.

I pick up a pamphlet about the discharge process.

“Did you read this one?”

“Not yet,” he says, and I notice he looks scared. “We’re just…not there. Not yet.”