“I don’t think I’ve ever seen someone like me with eating disorders represented in the media,” confesses Clémence, a young digital project manager and black feminist YouTuber. “For the longest time, anorexia and bulimia concerned only white teenage girls and supermodels. I think it’s one of the reasons it took so long for me to put the correct words on my eating disorders.” It took me a decade to realize I was sick, confessing to my GP at twenty years old that I spent my whole life either eating too much, eating nothing or trying to take laxatives or make myself vomit.

Growing up in France, Clémence always wanted to embody her mother’s idea of a perfect daughter – polite, obedient and thin. “Black women are, unfortunately, straightforward targets for eating disorders because of the way society constantly reminds us how unattractive and unworthy we are,” she reflects.

What Clémence’s mother listed as requirements say a lot about the culture of being the perfect black woman. Writer Stephanie Covington Armstrong added fierce, funny and social to this ongoing checklist as a kid. This helped her hide her issues with food. In her memoir Not All Black Girls Know How to Eat, she writes: “I became aware of the racism surrounding my disease: because I was a black girl with natural hair who had grown up below the poverty line, no one ever suspected I could be bulimic.”

As counsellor Edwina Hawkridge describes, we need to redefine our ideas surrounding black femininity. “The perception of ‘black women are fierce’ is an unhelpful narrative and part of the problem regarding black women not getting the help and support they need,” she explains. “It takes a different kind of strength and vulnerability to get outside help from a professional when you need it.”

It took me being far away from my family for me to finally seek help. Firstly with a therapist and her talking group in Paris, and then with Addictive Eaters Anonymous in London. All the while reading as much as possible about bulimia online. Suddenly, I wasn’t alone anymore. What people were saying had been buzzing around in my mind for years, we were all suffering from the same sickness in the end. We just weren’t represented anywhere.

Both representation and doctors ignore non-white ED sufferers

When it comes to eating disorders in communities of color, the rates are staggering. Black teenagers are 50% more likely than white ones to exhibit bulimic behaviour, such as binging and purging (Goeree Sovinsky, Ham & Iorio, 2011), yet they are less likely to be diagnosed by doctors in comparison with white counterparts (Becker, 2003). The same goes for black adult women.

This is likely due to a lack of diversity within eating disorder doctors and researchers. In her book, Covington Armstrong addresses her experience applying for a research study on EDs. Being the only black woman in the room, scholars rushed to see her. She left and never came back.

This discrimination does not stop at university; throughout my research, it became clear that therapists and eating disorders practitioners don’t see the disease through an intersectional lens at all. In dedicated clinics, patients learn how to plan meals. But these would never take into account one’s habits of spicy Indian food, eating with chopsticks or being a vegetarian. They will hide behind labels like generic or neutral meal plans – meaning white and unseasoned. In the twelve-step program of Addictive Eaters Anonymous, I was assigned a food plan by my sponsor where no spices were allowed at all. I forced myself to eat raw veggies and tuna for a couple of days and gave up. It all felt like punishment. How was I supposed to instantly change the eating habits I’ve known my whole life? And how could that be a part of the recovery I so deeply needed?

According to counsellor Edwina Hawkridge, a woman of colour herself who specialises in eating disorders treatment in London, part of the solution is to start noticing the symptoms and signs on everyone. As EDs are her speciality, she believes in helping an individual in its entirety. “Until the signs are better recognised and people receive holistic treatment for all areas of their lives, not just the depression or just the ED or just the anxiety or just diabetes, it will be difficult to assert a change,” she says.

The roots of eating disorders are universal

To counsellor Hawkridge, the disease manifests “at a time where sufferers have a deficit of being able to cope with life stresses and, we establish these deficits in childhood and adolescence.” We could all suffer from EDs; it all depends on the stresses and traumas we’ve experienced. For Covington Armstrong, the issue was growing up in an impoverished family in New York with no father and a mom who struggled to show warmth. In her memoir, she writes: “I found myself starving alternately for affection and food until it became impossible to separate the two.”

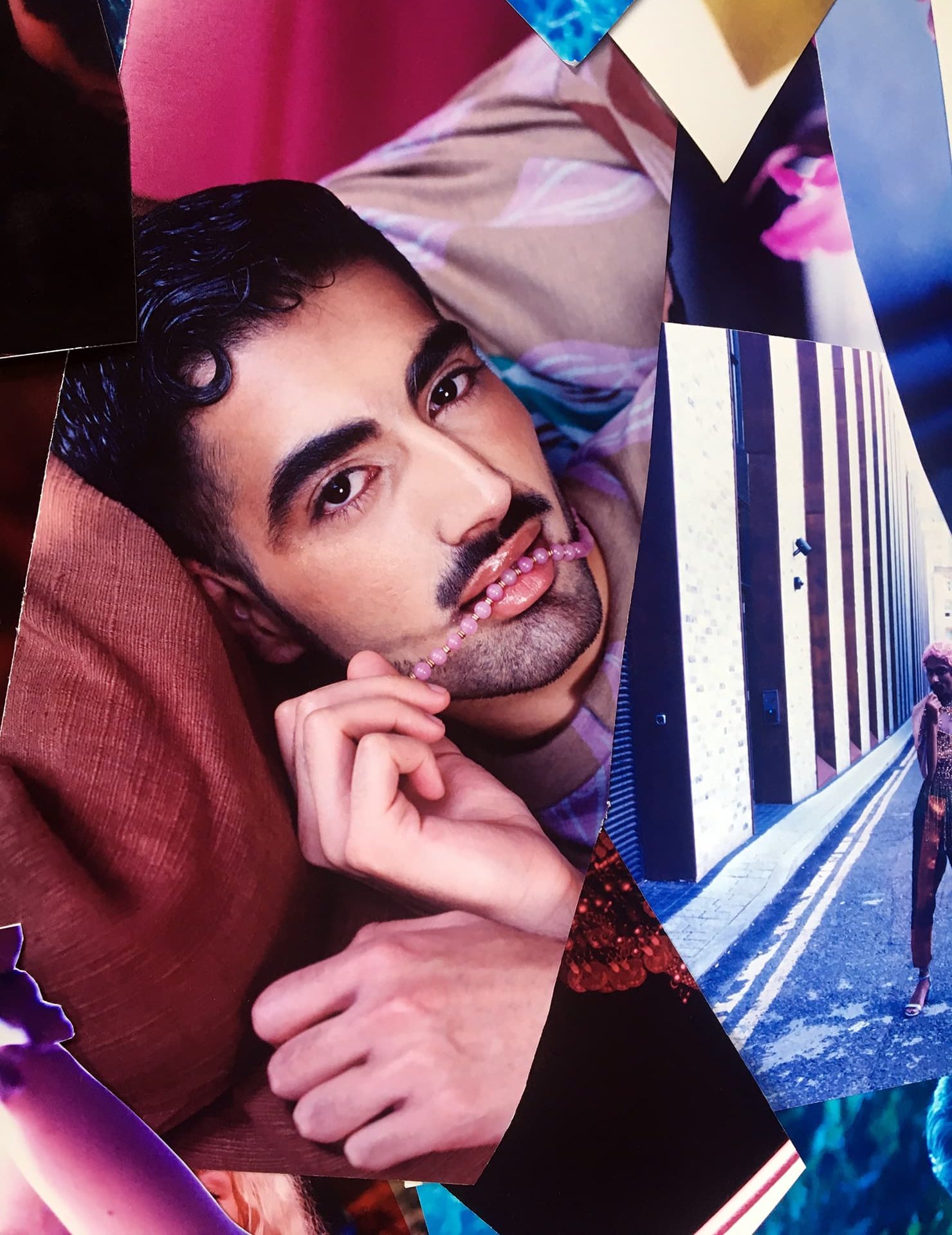

I feel a deep connection with Stephanie’s story. However, as a Black man, I’m supposed to leave food problems and lack of affection to my mostly white fragile female counterparts. The patriarchy and post-colonial standards oppress men, especially men of colour to the extent that we’re not supposed to be vulnerable. Not only have I always been told that crying and talking were reserved for the women in my life, but I was also taught to remain silent if I were to have any personal struggles. I had to keep everything in like a man. In the end, the only way our internal traumas are allowed to surface are through violence and anger. Should we have an addiction, it could only be as masculine as alcohol, drugs or sex. And we’re not the only ones.

For Aline, a young trans girl living in France, the oppressions doubled when she started transitioning. “I had always struggled with eating disorders, years before I came out. But being perceived as a woman today makes me more insecure about my weight and figure than ever, she explains. We are bombarded with injunctions, and it makes me feel awful because people don’t realise that what they expect as “the feminine body” is not what I live with. It takes me back regularly to the fact that I’m not a real woman in the eyes of so many people.”

According to Edwina Hawkridge, we could all suffer from eating disorders because the only requirement is self-reproach. The fertile ground lies in all of us: “I think under-representation always makes it harder for people to ask for help. But EDs are a mental illness that swathes themselves in shame. Shame is one of the predominant reasons people don’t seek help.”

I would have never pictured myself at seven years old talking to my mom about the ogre inside me who could not stop eating. She would have laughed at me while my dad would have never even listened. Everything around me was built to keep me silent. To fight back, we must build platforms, give the mic to people who can and want to tell their story and make non-white cis, trans, and non-binary individuals visible on the screen – starting the revolution against shame.